A New Role and a Bold Mission

Three years ago, I stepped into the role of Middle Years Programme (MYP) Coordinator at the International School of Hellerup (ISH). Almost immediately, our Board presented me with a clear and challenging mandate: implement a schoolwide benchmarking system to track student progress. It was a bold mission, especially in a school community that had never emphasized standardized testing. I recall sitting in that boardroom, equal parts excited and anxious, realizing that this initiative could profoundly shape our school’s future. Little did I know then what a transformative journey we were about to undertake.

From day one, I understood that this task was about more than just introducing tests—it was about shifting mindsets. ISH is an IB World School in Denmark, a country where traditional standardized tests are not a staple of education culture. In Denmark, the educational approach “avoids class rankings and formal tests; instead, children work in groups and are taught to challenge the established way of doing things”. Likewise, the IB’s MYP philosophy prioritizes teacher-created assessments and holistic skills over one-size-fits-all exams. In fact, “MYP assessment focuses on tasks created and marked by classroom teachers” rather than external exams. Introducing any form of schoolwide testing would have to be done with great sensitivity to these principles. I saw my new role as not only implementing a tool, but bridging two worlds: our skills-based, inquiry-driven IB framework and the data-driven insights that a good benchmarking system could provide.

An IB School in Denmark – Where Tests Aren’t the Norm

As I settled into my role, I took stock of our context. Here we were, an international MYP school in Denmark, proudly non-traditional in our assessment approach. Our students come from all over the world – different countries, curricula, and educational backgrounds. Some had never taken a formal exam; others came from systems rife with high-stakes tests. We also serve many EAL (English as an Additional Language) students and those needing learning support. This diversity is our strength, but it posed a challenge: How could we find a benchmarking assessment that was fair and meaningful for everyone?

Our starting point was essentially a blank slate. Unlike schools in exam-focused cultures, we had no legacy of routine standardized assessments to fall back on. In some ways, that was liberating – we could craft our approach from scratch – but it was also daunting. I remember conversations with teachers who were wary. Some veteran educators reminded me that “formal tests” just weren’t part of Danish or IB school life. We prided ourselves on project-based, student-centered assessments, so there was an understandable fear that benchmarking might herald a shift toward teaching to the test. I shared that concern, deeply. If this initiative even hinted at undermining our IB ethos, it would not succeed. Therefore, from the outset I was determined to frame benchmarks not as an alien imposition, but as a tool to enhance our existing practices – a way to measure what matters without sacrificing our principles.

The Search for the Right Benchmark

Finding the right assessment tool was the first critical step. The Board’s charge was urgent, but I knew a misstep here could derail the whole effort. We needed an assessment that was internationally normed yet flexible, skills-focused rather than curriculum-specific, and accessible to students still mastering English or needing support. Early on, we reviewed a number of well-known standardized tests in literacy and math. However, many of these tools assumed a homogeneity our student body simply didn’t have. For example, one popular reading test we examined was packed with idioms and cultural references that would stump a student who had only been learning in English for a year. Another math assessment expected vocabulary knowledge that our learning support students found confusing. These experiences reinforced my belief that any chosen tool must not punish students for language or background differences, but instead accurately capture their understanding and skills.

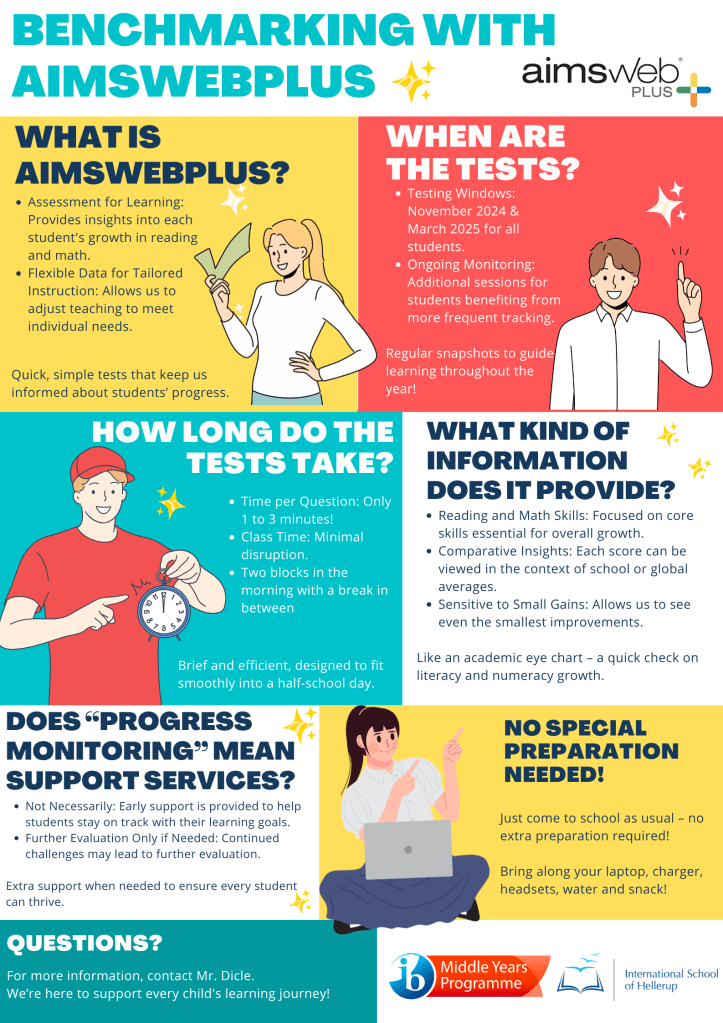

In fact, this wasn’t my first encounter with the benchmarking dilemma. In my previous role as EAL Coordinator, I had conducted internal research on various assessment systems to help monitor our English learners’ progress. One name kept resurfacing from that research: Aimsweb Plus. Back then, I was intrigued by its design – it offered “nationally-normed, skills-based measures” for literacy and numeracy and was built to support a range of learners. I even ran a small pilot of Aimsweb Plus with a few EAL students, impressed by how quick and focused the tests were (about 20 minutes each) and how the results pinpointed specific skill gaps without overwhelming the students. Those early impressions stuck with me.

So, when it came time as MYP Coordinator to choose a schoolwide benchmarking tool, I found myself gravitating toward Aimsweb Plus. I revisited my notes and reached out to peers in other international schools. The feedback was encouraging: Aimsweb Plus was praised for being efficient, user-friendly, and robust in data reporting. It is a system designed for universal screening and progress monitoring, providing percentile benchmarks against a national norm group while also giving measures like Lexile reading levels that teachers could easily use. Importantly, it was formative in nature – meaning it could guide teaching, not just summarize it. This aligned perfectly with our needs. Armed with this information, I proposed Aimsweb Plus to the Board and our pedagogical leadership team, explaining that it fit our profile: a tool to make student growth “visible, measurable, and meaningful” without turning our classrooms into test-prep centers.

Building a Community of Understanding

With the decision made to adopt Aimsweb Plus, the real work began – bringing our community on board. The best tool in the world would fail if our stakeholders didn’t understand or trust it. I knew we had to roll out the benchmarking initiative strategically and sensitively, with lots of communication and reassurance. Over the next several months, our focus was on building understanding among teachers, students, and parents about what these assessments were (and were not).

I developed a rollout plan that prioritized transparency and support. Some key actions in our plan included:

- Student Assemblies: We held grade-level assemblies to talk to students about the upcoming benchmarks. Standing on the auditorium stage, I explained in simple terms why we were adding these assessments. “Think of it like a check-up on your learning,” I told them, “just like you get a health check-up. It’s not a test you can fail – it’s a tool to see how we can help you learn even better.” We assured them it wasn’t going to affect their report grades and that it was okay to just try their best. By demystifying the process, we wanted to reduce anxiety and even spark a bit of curiosity among students about their own learning data.

- Teacher Workshops: Before the first student ever sat for a benchmark test, we organized professional development sessions for teachers. I shared research, walked through sample Aimsweb questions, and discussed how the data could inform instruction. We emphasized that these were not high-stakes tests, but short, formative check-ins on core skills. Together, we brainstormed how benchmark data might complement the rich assessments teachers were already doing in class. By involving teachers early and inviting their questions and concerns, we built a sense of collective ownership.

- Parent Information Sessions: For our diverse parent community, we hosted evening online meetings (which proved convenient for busy schedules). In these sessions, I outlined the purpose of benchmarking and how it aligned with our mission. Many parents in our international school had experience with rigorous exams in other systems, so some were relieved to hear these were low-pressure assessments. Others, new to the concept, had frank questions: Will this label my child? What if my child is a late bloomer? We addressed each concern, explaining that **benchmark results would never be used to stigmatize, but to help each student grow. I even shared the planned schedule – one literacy and one math benchmark in fall and spring – to show we were not excessively testing. By the end of these meetings, parents expressed appreciation for the school’s effort to gauge progress while keeping student well-being central.

- Board and Leadership Updates: Throughout the rollout, I kept the Board and school leadership closely informed. They had initiated this, after all, and it was important to demonstrate that we were proceeding thoughtfully. I provided short briefing reports on the training, sample data from our pilot runs, and how teachers were responding. This open communication ensured the Board remained confident and could themselves articulate to any community members why this change was a positive one. Their support was crucial, especially in those early days.

Every step of the way, our message was consistent: Benchmark assessments are tools for reflection and growth, not judgment. We said this over and over until it became almost a mantra. In meetings and newsletters, I highlighted that these assessments would “give timely insight into how students are developing key skills — specifically in literacy and numeracy”, helping us answer questions like are our students making expected progress, who needs support, and how do we challenge our high achievers. By positioning the benchmarks as a mirror and a map – reflecting where students are and mapping where to go next – we gradually eased the skepticism.

Overcoming Resistance Through Culture and Care

Despite our proactive communication, there was indeed some early resistance. A few teachers, especially those who had been at ISH for many years, admitted privately that they felt this might be the start of “creeping standardized testing.” In our first faculty forum on the topic, one colleague voiced what others were perhaps thinking: “We left national systems to get away from things like this.” I heard them out and acknowledged that, coming from a country with no strong test tradition, their caution was justified. These frank conversations became the foundation of trust. I made it clear that I had no intention of letting benchmarking turn into an unhealthy pressure cooker in our school. My promise to the faculty was that we would constantly review and adjust the process together, ensuring it remained a servant to learning, not the master.

One strategy that helped turn the tide was involving teacher leaders and early adopters. After the first round of benchmarks was administered, we held a reflective debrief. Some of our skeptical teachers were pleasantly surprised – the sky hadn’t fallen. In fact, many students finished the tests calmly, some even commented that it was “like a puzzle” or “kind of fun” to see what they knew. When we looked at the initial data reports, there were clear, actionable insights. I remember a math teacher, previously unconvinced, saying “I suspected several students were struggling with basic number operations, and the data really pinpointed who. Now I know exactly whom to give a bit more help – and in which areas.” Moments like that, multiplied across departments, began to soften the opposition. Teachers started to see the assessments not as a verdict on their teaching, but as another lens to understand student needs.

Cultural change takes time, but by the second cycle of testing, acceptance grew. We normalized conversations about percentile bands and growth scores in our meetings, always with the caveat that these were just one piece of the puzzle. I often used a line in those days: “We’re not just collecting scores — we’re collecting insights.” This phrase (one I personally hold dear) encapsulated our approach: the data was there to help us celebrate student growth and take action where needed. Gradually, the narrative shifted. Instead of dreading “an extra test,” teachers and students began to view benchmarks as a regular part of our learning journey – a chance to pause and reflect mid-year, much like the personal project or service reflections that IB students do. By aligning the language of benchmarking with the reflective culture of the IB, we saw fears give way to curiosity and even enthusiasm.

Turning Data into Action

With the community largely on board, the true value of the benchmarking system emerged in how we used the data to support students. Gathering scores means little if it doesn’t translate into better teaching and learning. As the results from the first full year rolled in, our Professional Learning Teams (PLTs) – small teams of teachers by grade level and subject – dove into the data. Those PLT meetings became goldmines of insight. We identified trends, shared surprise findings, and most importantly, made plans. The data helped flag students who could benefit from an extra boost and also those who needed more challenge, allowing us to respond proactively rather than reactively.

For our students needing support, we were now catching issues much earlier. For instance, if a student’s literacy benchmark showed they were “Well Below Average” in reading comprehension, that was an early warning. Within days, our Learning Support and EAL specialists coordinated with that student’s teachers to plan interventions. We set up small-group sessions targeting the specific skill gaps – be it vocabulary development or reading fluency – identified by Aimsweb’s detailed reports. These weren’t high-stress pullouts, but rather “booster” sessions built into the schedule in a low-key way. The philosophy was: intervene early, intervene kindly. By doing so, we often prevented a small gap from widening into a big problem. As one of our learning support teachers put it, “It’s like giving vitamins to the kids who need it, rather than waiting to treat an illness.”

Meanwhile, for our high-flyers, the data ensured they weren’t overlooked either. If a student scored “Well Above Average” in math, we didn’t just pat them on the back – we looked at how to keep them engaged. Teachers came up with enrichment activities: independent inquiry projects, advanced problem-solving challenges, or peer-teaching opportunities. One student, who breezed through the numeracy benchmark, ended up designing her own statistics project with her teacher’s guidance. The benchmarks essentially illuminated both ends of the spectrum, reinforcing a core IB tenet that each student should be appropriately challenged. Our approach became very much in line with what we had envisioned: using benchmark data alongside classroom assessments and observations to ensure every learner gets the right balance of support and challenge.

I vividly remember one PLT meeting where we reviewed the progress of a quiet 7th grader who had struggled in the fall benchmark, scoring in a low percentile for literacy. Through targeted help and perhaps the student’s own growing confidence, his spring benchmark jumped significantly. It was concrete proof of growth. When we shared that progress with him, his eyes lit up — he could see his improvement quantified. That moment drove home the point for all of us: this isn’t about numbers for numbers’ sake; it’s about personal growth. From then on, many students began taking ownership of their results, setting goals like improving their reading level or mastering their times tables, not for a grade, but for themselves.

Seeing the Culture Change and the Results

Now, three years in, benchmark assessments have become an embedded part of our school culture. It’s striking to think how far we’ve come. A process that once raised eyebrows is now routinely embraced each semester as part of our rhythm. Walking through the corridors during benchmark week now, I sense an atmosphere of calm purpose. Teachers are prepared and students approach the computer-based tests with confidence, understanding that this is just another way to reflect on their learning.

The results we’ve gathered over the years tell a powerful story. We can confidently report that over 90% of our MYP students consistently score in the average or above average bands in both literacy and numeracy. More importantly, we see growth from fall to spring in nearly every case – even students who start behind are advancing, many catching up to international norms or beyond. Our “risk level” flags, which initially identified a handful of high-need cases, have mostly receded to green; nearly all students now show low risk by year’s end, on track to meet or exceed expectations. This trajectory speaks not just to the power of data, but to the incredible work of our teachers in response to that data. It has validated that our inquiry-based IB approach, combined with strategic data use, yields tangible academic gains. As our Academic Progress Reports have highlighted, students at ISH are performing well above national expectations in core skills, and doing so without sacrificing the joy and engagement of learning.

See the most recent report here (Academic Progress Report 2024-2025)

Another significant outcome has been alignment among all our stakeholders – a true community buy-in. Parents, initially cautious, now appreciate receiving benchmark reports alongside narrative feedback. It gives them an added perspective on their child’s progress. One parent told me that the benchmark report helped her understand her son’s strengths in math better, and even encouraged him to read more at home to raise his Lexile level. The Board, too, is pleased to see that their strategic vision paid off. We regularly share compiled data and analysis with the Board and even the Danish Ministry of Education when required, demonstrating with confidence that our students are thriving and any gaps are promptly addressed. This has bolstered trust in the school’s direction and provided a “roadmap for continued success,” as I noted in our latest report. There’s a sense of unity now – teachers, students, parents, and leadership all pulling in the same direction, informed by a common understanding of our goals and how we measure progress toward them.

On a personal level, the journey has been immensely fulfilling. Not only do I see measurable student growth, but I also see something less quantifiable yet just as important: a culture of reflective improvement. Our faculty discussions are more evidence-based; our students are more self-aware learners. We have, in essence, become a data-informed learning community without losing our soul. And for me as a coordinator, that balance is perhaps the achievement I’m proudest of.

Reflecting on IB Ideals and Data-Informed Teaching

Looking back, I realize this journey was as much about leadership and learning as it was about assessment. There were moments I questioned if we were doing the right thing, moments I had to persuade and sometimes gently push, and moments I had to step back and let the data speak for itself. A key leadership insight for me was the importance of empathy and communication in change management. Listening to concerns, being transparent about intentions, and sharing early wins helped build the trust that was crucial for success. Change didn’t happen overnight; it was a slow build of understanding layer by layer. But that solid foundation means the change is now sustainable.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway is that IB philosophy and data-driven practices are not adversaries, but allies when combined thoughtfully. Our experience at ISH proves that a school can maintain its commitment to the IB’s skills-based, conceptual framework and embrace data to enhance teaching. In fact, our benchmarking initiative ended up reinforcing many IB ideals. We encouraged students to be reflective, one of the IB Learner Profile traits, by looking at their own progress metrics. We prompted teachers to be inquirers and open-minded, examining results and trying new strategies in response. The benchmarks became not an external add-on, but part of our reflective cycle of continuous improvement, aligning with our vision of nurturing purposeful, responsible learners. As I noted in a recent school newsletter, this benchmarking effort “aligns with the IB learner profile and our vision of nurturing reflective, purposeful, and responsible global citizens”. That alignment has been key.

Today, when I walk through our halls, I often think back to three years ago. The contrast is striking – from initial skepticism to a school culture where data-informed instruction is the norm. One could say we built a “strong foundation for the future” by carefully integrating benchmarking into our practices. It’s a foundation that future cohorts of students will benefit from, and it’s one that can weather changes because it’s grounded in our shared values.

To fellow educators considering a similar path, I offer our story as reassurance and inspiration. Thoughtful assessment implementation, done with care for community and respect for culture, can indeed positively transform a school. It requires patience, collaboration, and a steadfast focus on why we do it – for student growth. When done right, you’ll find that data doesn’t dampen an inquiry-based, student-centered environment; instead, it enriches it. We’ve seen firsthand that combining the IB’s holistic approach with smart, compassionate use of data leads to the best of both worlds – students who not only learn deeply, but who can also see and celebrate their growth in tangible ways.

As I finish this reflection, I am filled with gratitude and hope. Gratitude for the colleagues, students, and parents who took this leap of faith with me, and hope for what’s next. Implementing a schoolwide benchmarking system was a journey of change, but it became a journey of growth for all of us. In measuring what matters, we ultimately proved that what matters most is how you use those measures to uplift every learner. And that is a lesson I will carry forward in every chapter to come.

Sources

- International Baccalaureate. (n.d.). Middle Years Programme: Assessment and exams. Retrieved from: https://www.ibo.org/programmes/middle-years-programme/assessment-and-exams/

- OECD. (2016). Education Policy Outlook: Denmark. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/education/DENMARK-Education-Policy-Outlook.pdf

- Renaissance Learning. (n.d.). AimswebPlus Overview. Retrieved from: https://www.renaissance.com/products/aimswebplus/

- Dicle, R. (2025, April 23). Measuring What Matters: How Benchmark Assessments Help Our MYP Students Thrive. International School of Hellerup. Retrieved from internal school newsletter/report.